[fblike]

by Bill Thompson

Bill Thompson competed in college for Western Kentucky University (WKU) in extemp, debate, impromptu and other events during the early 1990’s. Mr. Thompson was WKU’s first national finalist and first champion in limited prep at a national tournament. Thompson started coaching high school extemp in 1993 and has coached extempers to four state championships and numerous state finals. In the last decade he has had extempers in numerous national elimination rounds and had a student finish in the top six at the MBA Round Robin. In his daily life he is a case manager at a teen shelter for homeless/runaway/abused youth in Louisville Kentucky. DMC and MI are topics that he deals with daily and is passionate about. Questions about this brief can be sent to mobilemrbill@gmail.com or feel free to approach him at a tournament to discuss these or other extemp issues.

Preface

If you were to poll extempers from the beginning of the activity to now and ask them what their least favorite topic area is for a round, overwhelmingly “Domestic Social” would be their answer. This is important to understand for a few reasons. Initially, that means if you can build a comfort level with these topics you can put yourself in a position to outshine your competitors when these rounds happen. Additionally, since extempers don’t like these rounds they typically don’t file for these types of questions and thus don’t understand the impact of social issues. It is ironic that most extempers are more aware of the Foreign Policy implications of maintaining Gitmo than they are the domestic implications of the topics covered in this brief. Finally, while rare, these rounds occur at the biggest tournaments of the year and thus warrant better examination by those serious about being competitive nationally in extemp.

Last year the final round of the Wake Early Bird was “Domestic Poverty”. With this in mind, it is logical to assume that another domestic social round could end up as the final this year. When discussing potential topics for a brief with Logan, this DMC/MI stood out for a few reasons to me.

- They are intersectional topics that touch on so many other domestic social issues. (Poverty, Race, Child Welfare, Education, Public Health, Drugs, etc.)

- Eric Holder’s sentencing initiatives, state drug legalization efforts, state initiatives like Kentucky’s concerning juvenile confinement, & other factors make this a timely topic area for discussion.

- This is an issue spiraling out of control at an exponential rate. The implications of DMC & MI continuing on their current trajectory could have horrendous impacts on local, state, & federal levels in terms of cost of confinement alone.

Age Demographics

Incarceration in America can most clearly be split in to juvenile and adult incarceration. This is the clearest split when addressing issues concerning confinement, because there is a clear dividing line between how these groups go through the criminal justice system and how they are confined once convicted. The obvious exception to this occurs when juveniles are tried as adults or when juveniles begin their incarceration as juveniles and then are moved in to adult facilities when they reach the age their state designates for adult incarceration.

I. Juvenile Incarceration

The first correctional facility, built solely for juveniles, was built in Chicago Illinois in 1899. However, juvenile justice as it functions today, was created 40 years ago with passage of the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act. The Act was initially created with the intention of decriminalizing status offenses and separating incarcerated juveniles from their adult counterparts by both “sight and sound”. In order to oversee compliance with this act, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) was created. In the last 20 years OJJDP has expanded their efforts concerning juvenile incarceration to look at issues like DMC. Unlike adult incarceration, statistics indicate that OJJDP has been successful in reducing confinement rates.

http://www.ojjdp.gov/ojstatbb/ezacjrp/asp/selection.asp allows you to look at confinement through multiple layers for those interested.

While OJJDP has made great strides in reducing juvenile confinement rates that is not to say there aren’t still areas where progress can be made. This is important because juveniles are one of the few age demographics currently growing in the US.

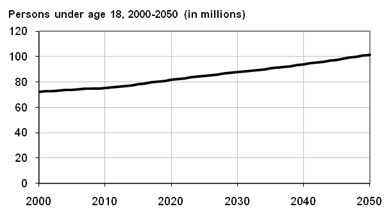

- The juvenile population is expected to grow at a faster rate than the adult population in the coming decades. Based on the latest population projections from the U.S. Census Bureau, between 2015 and 2025, the population of persons under age 18 is expected to increase 5%. In contrast, the population of persons ages 18 through 24 will decline 3%, persons ages 25 to 64 will increase 3%. Only the population of those ages 65 and older is expected to increase more than the youth population (36%) by 2025.

- The population of juvenile minorities will experience the most growth between 2015 and 2025. The number of black, non-Hispanic juveniles is expected to increase about 5%, American Indian/Alaskan Native, non-Hispanic juveniles 3%, Asian, non-Hispanic juveniles 17%, and Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islanders non-Hispanic juveniles 15%, while white, non-Hispanic juveniles will decline 4%. Juveniles of Hispanic ethnicity are expected to increase 17% by the middle of the next decade, and the number of multi-racial youth is expected to grow nearly 30% during this period.

- By 2025, racial-ethnic minorities will account for 53% of the youth population under age 18, and 60% by year 2045.

Internet citation: OJJDP Statistical Briefing Book. Online. Available: http://www.ojjdp.gov/ojstatbb/population/qa01101.asp?qaDate=2012. Released on December 17, 2012.

This population growth is important because if DMC is an issue and this data suggests that minorities are going to be a majority in our lifetimes, then the issue of institutional racism needs to continue to be a priority of OJJDP moving forward.

One of the issues that make fighting MI and DMC in juvenile corrections difficult is the fact that juvenile court proceedings happen behind closed doors with little to no review. Assuming nothing corrupt ever happened in juvenile courts, this fact is still problematic because it means that it is impossible to establish any kind of precedent for judicial rulings. That said, there is corruption in juvenile corrections. In states where Child Protective Services (or whatever name that state uses) is funded through county budgets, local judges (who are elected) have a built-in incentive to criminalize behaviors like running away rather than referring these youth to services aimed at investigating abuse. Put simply departments of juvenile justice facilities (funded by state coffers) have a built-in incentive over pursuing placements like foster homes (locally funded) because of the potential negative impacts to judge’s reelection hopes due to the cost their rulings had on their voters. More explicit corruption can be seen in cases like the “Kids for Cash” scandal in Pennsylvania.

Perhaps the most compelling argument for taking juvenile incarceration as a serious issue is presented by Neil Bernstein.

“The U.S. rate of juvenile incarceration is seven times that of Great Britain, and 18 times that of France. It costs an average of $88,000 a year to keep a youth locked up, far more than is spent on a child’s education. The biggest problem with juvenile incarceration, author Nell Bernstein tells NPR, is that instead of helping troubled kids get their lives back on track, detention usually makes their problems worse, and leads to more crime and self-destructive behavior. “The greatest predictor of adult incarceration and adult criminality wasn’t gang involvement, wasn’t family issues, wasn’t delinquency itself,” Bernstein says. “The greatest predictor that a kid would grow up to be a criminal was being incarcerated in a juvenile facility.”

It is because of this fact, that Benstein’s latest book argues for the abolition of juvenile prisons. Also, the substandard conditions of juvenile corrections are another argument against juvenile prisons. While it is unlikely this will ever occur, there is currently an effort being put forth to further decrease the number of youth being incarcerated annually for nonviolent offenses. An example of these efforts is SB 200 which passed in Kentucky in April of this year.

Put simply, Michelle Alexander argues in her book, The New Jim Crow that, “Many offenders are tracked for prison at early ages, labeled as criminals in their teen years, and then shuttled from their decrepit, underfunded inner city schools to brand-new, high-tech prisons.”

“We could choose to be a nation that extends care, compassion, and concern to those who are locked up and locked out or headed for prison before they are old enough to vote. We could seek for them the same opportunities we seek for our own children; we could treat them like one of “us.” We could do that. Or we can choose to be a nation that shames and blames its most vulnerable, affixes badges of dishonor upon them at young ages, and then relegates them to a permanent second-class status for life. That is the path we have chosen, and it leads to a familiar place.”

II. Adult Incarceration

A. Statistics About Incarceration.

The facts about MI are staggering even if they have shown moderate improvement in recent years. To understand the implications of MI, I will offer the following statistics. It is important to remember that data is typically only available a few years after the fact.

HIGHLIGHTS (http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/p12tar9112.pdf)

- In 2012, the number of admissions to state and federal prison in the United States was 609,800 offenders, the lowest number since 1999.

- The number of releases from U.S. prisons in 2012 (637,400) exceeded that of admissions for the fourth consecutive year, contributing to the decline in the total U.S. prison population.

- New court commitments made up 82% of state admissions in 1978, 57% in 2000, and 71% in 2012.

- New court commitments to state prisons for drug offenders decreased 22% between 2006 and 2011, while parole violation admissions decreased 31%.

- Between 1991 and 2011, new court commitments of females to state prison for violent offenses increased 83%, from 4,800 in 1991 to 8,700 in 2011.

- Drug offenses accounted for 24% of new court admissions of black inmates in 2011, a decrease from a range of 35% to 38% from 1991 to 2006.

- Since 1991, the proportion of newly admitted violent offenders receiving prison sentences of less than 5 years has increased.

- California’s Public Safety Realignment policy drove the decrease in the total number of admissions to California state prisons, as well as a decline in the proportion of admissions to California state prisons for parole violation (from 65% in 2010 to 23% in 2012).

- Prisoners aged 44 and younger accounted for 80% of prison admissions, 77% of releases, and 72% of the yearend population in 2012.

- The number of prisoners sentenced to more than 1 year under state or federal correctional authorities in 2012 was 1,511,500, down from 1,538,800 at yearend 2011.

The Center for Law and Justice (http://www.cflj.org/new-jim-crow/new-jim-crow-fact-sheet/)

We imprison more people than any other country

- The U.S. has over 2.4 million behind bars, an increase of over 500% in the past thirty years

- We have 5% of the world’s population; 25% of its prisoners

- People of color represents 60% of people in cells

- One in eight black men in their twenties are locked up on any given day

- 75% of people in state prison for drug convictions are people of color although blacks and whites see and use drugs at roughly the same rate. In NYC, 94% of those imprisoned for a drug offense are people of color.

- The number of drug offenders in state prison has increased thirteen-fold since 1980

- 5.3 million Americans are denied their right to vote because of a conviction

- 13% of black men are disenfranchised (can not vote)

By age 18, 30 percent of black males, 26 percent of Hispanic males and 22 percent of white males have been arrested.

By age 23, 49 percent of black males, 44 percent of Hispanic males and 38 percent of white males have been arrested.

While the prevalence of arrest increased for females from age 18 to 23, the variation between races was slight. At age 18, arrest rates were 12 percent for white females and 11.8 percent and 11.9 percent for Hispanic and black females, respectively. By age 23, arrest rates were 20 percent for white females and 18 percent and 16 percent for Hispanic and black females, respectively. –January Journal of Crime & Delinquency

Check back tomorrow for part II of this brief.

1 Pingback