[fblike]

The “Arab Spring” of December 2010 created uprisings throughout the Middle East and North Africa and successfully brought down the existing governments of Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya. As extempers are aware, the Arab Spring, which has also been referred to as the “Arab Uprisings” by some Middle Eastern historians like Dr. Juan Romero of Western Kentucky University, has not produced more stability in the region and some countries that were affected are sliding back toward despotism. Egypt has a short-lived post-revolutionary government under the Muslim Brotherhood that was deposed by the Egyptian military in the fall of last year and Libya is struggling to regain its footing after deposing long time dictator Muammar Gaddafi (you will also see Gaddafi referred to in the media as “Qaddafi”). Libya is home to feuding tribal groups and militias, some of whom have seized the country’s ports and prevented oil from leaving the country. In some ways, Libya’s problems mirror those of Iraq after the United States invasion in 2003 where the central government, built around the personality of the main leader, collapsed and the interim government is finding it very difficult to piece the nation back together again. A big difference between the two is that the United States and its allies in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) never officially put “boots on the ground” in Libya, so the interim government there has struggled to maintain order. The Cato Institute has an interesting video that features a discussion of Libyan problems and it released this on March 19th.

The “Arab Spring” of December 2010 created uprisings throughout the Middle East and North Africa and successfully brought down the existing governments of Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya. As extempers are aware, the Arab Spring, which has also been referred to as the “Arab Uprisings” by some Middle Eastern historians like Dr. Juan Romero of Western Kentucky University, has not produced more stability in the region and some countries that were affected are sliding back toward despotism. Egypt has a short-lived post-revolutionary government under the Muslim Brotherhood that was deposed by the Egyptian military in the fall of last year and Libya is struggling to regain its footing after deposing long time dictator Muammar Gaddafi (you will also see Gaddafi referred to in the media as “Qaddafi”). Libya is home to feuding tribal groups and militias, some of whom have seized the country’s ports and prevented oil from leaving the country. In some ways, Libya’s problems mirror those of Iraq after the United States invasion in 2003 where the central government, built around the personality of the main leader, collapsed and the interim government is finding it very difficult to piece the nation back together again. A big difference between the two is that the United States and its allies in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) never officially put “boots on the ground” in Libya, so the interim government there has struggled to maintain order. The Cato Institute has an interesting video that features a discussion of Libyan problems and it released this on March 19th.

Libya is Africa’s largest oil producing nation and its successful transition to an effective democracy in a multiethnic country is a test not only of the Arab Spring, but also of the international community’s commitment to stability in North Africa. This topic brief will provide a brief history of Libya, analyze the country’s political, security, and economic problems, and provide some recommendations for how the international community and Libya’s political players can resolve some of the problems that the country currently faces.

Readers are also encouraged to use the links below and in the related R&D to bolster their files about this topic.

Brief History of Libya

From the mid-sixteenth century until the first decade of the twentieth century Libya was ruled by the Ottoman Empire. The Ottomans ruled a multiethnic empire that encompassed much of the modern Middle East and parts of North Africa and the Ottomans governed Libya as three separate provinces: Tripolitania (modern Tripoli), Cyrenaica, and Fezzan. Ottoman rule was very decentralized and lack of direct Ottoman control produced a civil wars and instability. It also produced problems with other nations like the United States, who had its commerce in the Mediterranean Sea affected by pirates operating out of Tripoli. It was only when reformers took control of the Ottoman Empire in the second half of the nineteenth century that any type of true, organized governance took place within Libya.

The second half of the nineteenth century saw the emergence of a unified Italy on the European continent and Italy was late to the colonial grabs in Africa that took place around that time period. Italy’s quest for an African empire resulted in their embarrassing defeat to Ethiopians in 1896 at the Battle of Adwa, which made them the first European nation to lose a war to an African state. Italy made another attempt at a colonial grab in 1911-1912 when it took advantage of the Ottoman Empire’s problems in the Balkans and seized control of Libya. Al Jazeera on March 18th explains that when Libya took control of Libya they went about uniting the three provinces of Tripolitania, Cyrenaica, and Fezzan under one administrative structure and it took decades of bitter fighting to make this a reality. In fact, Libya was not even called Libya until the Italians gave it that name in 1934. The Italian government of Benito Mussolini made a poor decision to unite itself with Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany in the Second World War and as a result lost control of Libya, which was governed by Allied forces until 1951.

After it received its independence, Libya established a constitutional and hereditary monarchy under King Idris. At first, the international community saw very little potential in Libya, since the country had very little economic infrastructure and foreign investment. However, oil was discovered in 1959 and this allowed King Idris to wean the country off of foreign aid and expand the size of the Libyan state. The oil wealth brought problems, though, as ordinary Libyans believed that the monarchy was using the resources for itself and not giving the Libyan people an adequate share and this led to a military coup that toppled the monarchy in September 1969.

The leader of that coup, Colonel Muammar Gaddafi eliminated the monarchy and established a republican form of government that assumed some democratic institutions like local congresses and a national parliament. However, Gaddafi was really the one pulling the strings and ruled the country as a dictator in all but name. Gaddafi was a believer in Arab socialism and Arab unity and he proclaimed that Libya’s identity was Arab to the detriment of minority groups in the country like the Berbers, who have long seen themselves as a distinct ethnic group from the first millennium BCE. Arab socialism called for governments in the Middle East and North Africa to wean themselves off of dependence on Western governments and argued for the nationalization of economic resources to provide greater wealth to its people. The ideology successfully won support for leaders like Gaddafi, but came at the cost of stifling foreign investment in Arab economies and reducing economic opportunities for young people. The emphasis on Arab unity also poisoned politics as leaders claimed they were the embodiment of their respective nations and were unwilling to tolerate dissent. By the late 1970s, Gaddafi unpopular in the West due to his support for terrorist groups and President Ronald Reagan had Libya bombed in April 1986 after a West Berlin discotheque that was frequented by American soldiers was attacked by terrorists associated with the Libyan secret service. In 1995, Gaddafi called for a jihad against the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), but moved away from his extreme rhetoric after the invasion of Iraq in 2003. Gaddafi voluntary surrendered his weapons of mass destruction and went about trying to create a “United States of Africa.”

Despite Gaddafi’s gradual moves away from extremism, the country was ripe for a revolution in 2011. By this time, Gaddafi had governed the country for forty-two years and a third of his nation still lived in poverty. Although Gaddafi’s beliefs in Arab socialism led to legal equality between men and women in employment and higher education and eliminated illiteracy, the country was still too dependent on foreign oil resources and had one of the highest unemployment rates in North Africa. Unrest also grew in Eastern Libya which saw very little infrastructure investment from the government even though it produced the bulk of Libya’s oil. Libyans also grew tired of corruption within Gaddafi’s circle as his family and close friends controlled business enterprises to enrich themselves at the expense of the population. Global dictators never seem to learn that living in luxury when a large portion of the population wants more jobs, infrastructure, and social security is a recipe for disaster. Another problem was that Gaddafi was intolerant of dissent and established a police state to spy on dissidents. The founding of political parties was illegal and dissident’s executions were publicized by the government to squelch rebel attempts.

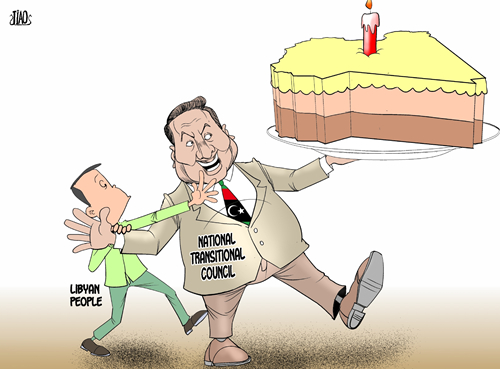

The Arab Spring arrived in Libya in February 2011 and the rebel forces soon consolidated their leadership in the National Transitional Council (NTC) that Western governments gradually came to endorse as Libya’s legitimate government. Gaddafi’s military forces successfully began beating back the rebels and it looked for a time that he would prevail, but the United States and European governments intervened in March 2011 by having the United Nations Security Council authorize the establishment of a no-fly zone to protect the Libyan people from Gaddafi’s forces. In theory, this would create a stalemate in the conflict by preventing Gaddafi’s forces from destroying the rebels. The UN resolution did not authorize regime change, which was a sticking point for Vladimir Putin and the Russian government. Still, the NATO-led “no-fly” campaign soon became an instrument of regime change as Libya’s ground forces and air forces were devastated by the NATO attacks and rebels began advancing under the cover of NATO firepower. The rebels captured Tripoli, Libya’s biggest city that houses a third of the country’s population, in August 2011 and Gaddafi was captured by rebels in the city of Sirte and summarily executed. The Obama administration and Western governments saw Gaddafi’s death as a successful end of the conflict and subsequently ended their military campaign. However, critics at the time warned that a power vacuum would emerge without Gaddafi and Reason on March 18th points out that NATO’s intervention may have accelerated the violence in the Syrian uprising due to rebels there thinking they would receive similar support. Extempers are aware that earlier this season President Obama tried to lead an effort to give that support, but a lack of public support for attacking Syria forced him to back down.

With Gaddafi’s death, pro-government resistance effectively crumbled and Libyans voted for officials in the General National Congress (GNC) in July 2012. The GNC was tasked with making arrangements for the drafting of a new constitution and giving Libya a legitimate government as it made the transition from the Gaddafi era to a new, more democratic one. However, political and economic problems have plagued Libya since the revolution and have harmed the GNC’s legitimacy and its ability to govern the country effectively.

Libya’s Political & Security Problems

The vote of the Libyan people in July 2012 for the General National Congress was a symbolic moment when Libyans were able to express their opinion in free elections for the first time in more than four decades. However, the GNC has come to embody many of the political problems in Libya by not living up to its mission, namely to create a new constitution for the country. The Christian Science Monitor on March 15th writes that shortly after it was established, the GNC has bickered over how the national constitution should be created. Some political forces favored having the committee appointed by the GNC, while others wanted elections to be held for a constituent assembly. Once it was decided that a popularly elected constituent assembly would do the work there was a dispute over the election law that would set the rules for that election. These political disputes weakened some of the energy of the revolution among the population and illustrated to millions of Libyans that the current government lacked a defined plan for creating new democratic institutions.

Libyan lawmakers finally came to a decision on how to create a constituent assembly, but they failed to make the body inclusive enough for Libya’s different ethnic groups. Foreign Policy on February 26th writes that the election law for the constituent assembly, which was passed in July 2013, only gave six seats in the constituent assembly to minority groups like the Tebu, Taureg, and Berbers (the native people of Libya). The small representation of these groups would allow them to be overrun by the Arab majority. For example, The Christian Science Monitor on March 23rd reports that the Berbers want the new constitution to make their language, Tamazight, an official language and to contain guarantees that the government will not interfere with or limit its use. Under Gaddafi, the Berbers were persecuted for their unwillingness to assimilate to Arab ways, so their suspicions of the new government are well-founded. As a result, when elections were held in late February for the assembly, only 45% of the 1.1 million voters who registered did so, which creates problems for the legitimacy of the constituent assembly since more than two million Libyans voted in the 2012 GNC elections. Part of the low turnout was due to the Tebu and Berbers boycotting the elections. The Foreign Policy article previously cited explains that there are also questions about how the constituent assembly will do its work because it has only been given four months to draft a new constitution and observers think that is not enough time. When the constituent assembly does finish their constitutional draft it must approved by the population in a referendum, so that will provide another test for how popular the document is among the Libyan people and will be a test of its legitimacy. Due to the slow nature of getting the constituent assembly established, the GNC arbitrarily extended its term in office on February 7th, which has also caused unrest among the population. Although Libya has told the Arab League that it plans to order elections soon for a House of Representatives, which will replace the GNC, the Libya Herald on March 26th writes that no date has been set for new elections and the GNC is showing no signs of dissolving itself as a political body. On Sunday, the GNC created a law for fresh parliamentary elections, but it is still up to an electoral commission to set the date of those elections, which is still unknown. The Economist on February 22nd writes that the GNC is deadlocked between Islamist parties, which wish to create a constitution based on Islamic law, and moderates who wish to modernize the country. After protests broke out against the government’s unilateral extension of its mandate it has promised quick elections, but all of this might play into the hands of extreme Islamists who argue that Libya’s problems with democracy show that it is no substitute for Islamic law.

In a parallel to the problems that Western governments faced in Iraq, Libya has disqualified officials who served under Gaddafi from participating in the new government. American historians and policymakers argue that the United States decision to purge the old Iraqi political and military leadership is what made the Iraqi insurgency worse after the downfall of Saddam Hussein in 2003. The Brookings Institution on March 17th provides a paper on this issue that extempers should download and read and it summarizes Libya’s Political Isolation Law (PIL), which the GNC passed in May 2013. The PIL’s ban on Gaddafi officials from serving in government has worked against stability because it makes experienced figures feel that they have no investment in the government (making them more likely to work with rebel forces) and also works against creating a democratic system based on consensus rather than revenge.

Libyan politics has also been very dysfunction due to the lack of security in the country. In the spring of 2012, attacks against the government grew from pro-Gaddafi militants and international security experts argue that al-Qaeda elements are now operating in the country. The Libyan government has called for the international community to help it fight a “war on terrorism” (ironically using the terminology of former U.S. President George W. Bush – President Barack Obama abandoned the “war on terrorism” terminology after taking office) and The Libya Herald on March 20th argues that the terrorist attacks that the government has witnessed are coming from Islamic militants and old government forces operating near Sirte. Terrorists in Libya have targeted military graduation ceremonies, public gatherings with car bombings, and in September 2012 they attacked the U.S. consulate in Benghazi in Eastern Libya, which led to the death of ambassador Chris Steven and three other Americans.

The war with Gaddafi’s forces devastated Libya’s existing military institutions and these have to be rebuilt from scratch. As a result, the existing Libyan government is held up by the support of militia groups, who back certain political figures. For example, The Economist of March 15th points out that militias around the city of Misrata give their support to the new prime minister, Abdullah al-Thinni, and the speaker of the GNC, Nuri Abu Sahmain. However, there are rival groups operating in the capital of Tripoli that support other politicians and that fear is that if Libya’s political problems become more acute that another civil war could be in the offing. The Guardian on March 23rd writes that the central government is currently paying off militia groups in order to maintain authority since there is not a strong national military to call upon. There are an estimated 160,000 men in these militias throughout the country and they are being paid $1,000 a month to protect airports, seaports, and other government installations. These militias are supported by an estimated 15,000,000 rifles and other weapons that have been funneled into the country from Arab states or obtained from Gaddafi’s old barracks. The Associated Press has an excellent article on the problems of Libyan security posed by these weapons on March 22nd when it writes that many of these weapons are now being exported to other conflict zones like Niger, Chad, Mali, and Syria and that this means that Libya is “exporting its insecurity to surrounding states.” Still, the idea of taking these weapons from militants is nearly impossible under the status quo since the central government does not have a well-trained national military to undertake the task and militia members are unwilling to give up their weapons until proper security forces can be established. After all, in a lawless land, who would hand over their only tool of leverage to a government that cannot live up to its promises and control the nation?

Libya’s Economic Problems

Since most of Libya’s economic activity centers around oil, the recent security situation has created many problems for the central government. The most publicized economic problem related to security exists in the country’s east, where a militia under the command of Ibrahim Jathran (whose name has also been written as “Ibrahim Jedran” in some Western sources) that was initially tasked with guarding the country’s oil ports in that area, mutinied over the summer and took control of them. The Washington Post on March 18th writes that Jathran is demanding an investigation by the GNC into corruption and embezzlement of Libyan oil funds and a fairer distribution of oil revenues among the regions of Tripoli, Cyrenaica, and Fazzan. The complaint of the Federalist militia in Cyrenaica, which is where Jathran is based, is that under Gaddafi the Libyan government has taken a great deal of oil out of Cyrenaica but its residents have received very little from the central government in terms of investment and infrastructure spending. Jathran has also called for Libya to return to its 1951 constitution because under that arrangement all three regions had more autonomy. The activities of the Federalists have created a major headache for the GNC because Slate points out on March 12th that 80% of Libya’s oil reserves are located in the east and the Federalists have refused to allow Libya to export this oil through their control of the ports in the area. The inability to export oil has been devastating for the economy, as the country is selling only 12.5% of its production capacity and losing an estimated $130 million a day.

The Federalists most brazen move in the area was recently trying to sell some of the oil in the region to an unidentified foreign buyer. The Economist on March 10th writes that on March 8th a North Korean-flagged ship called The Morning Glory docked in Es-Sider, the country’s largest oil-export terminal, and rebels loaded an oil shipment worth more than $30 million onto it. In essence, this was a direct shot at the GNC’s authority because the Federalists were trying to acquire revenue by selling Libya’s most valuable natural resource. The incident became more odd when the Agence France-Presse writes on March 23rd that North Korea denies that it was in charge of the ship. When The Morning Glory set out for the Mediterranean, the Libyan government warned that it would sink the ship, but its navy, which was devastated in the NATO attacks of 2011, proved incapable of doing so. After receiving permission, a team of U.S. Navy SEALS boarded the ship on March 16th and took it over without incident. The ship was then returned to Libyan authorities and Reuters writes on March 19th that the UN Security Council has now authorized any member state to board ships that have contraband oil from Libya. Ships that try to load at militia-controlled ports outside of the GNC’s jurisdiction will also be subject to blacklisting by the UN Security Council’s sanctions committee, which would result in them being barred from international commerce.

The Morning Glory incident reveals the dangers facing the current Libyan regime. Foreign Policy on March 18th writes that since oil is so vital to Libya’s economy and since most Libyans hold jobs funded by oil revenue, if The Morning Glory had succeeded in transferring its cargo to a buyer that it would have completely undermined the central government and it would have been open season for other international actors to pillage the country’s oil resources. The incident has created more political unrest in Libya as Prime Minister Ali Zeidan was ousted from office in a no confidence vote and replaced by Defense Minister Abdullah al Thinni. Zeidan took over in October 2012 after the first post-revolution prime minister Mustafa Abu-Shagur was also ousted in a no confidence vote and he was actually kidnapped by unhappy militia members in that same month (he was released after several hours without incident)! Zeidan now stands accused of corruption and embezzlement, but has fled to Germany. The Christian Science Monitor writes on March 11th that Libyan legislators have been pressured to enact laws by militia groups and violence has become a norm in national politics at party meetings and gatherings. For all intents and purposes, militia leaders are doing whatever they want and the Federalists are harming the national economy by blocking the nation’s oil shipments. The GNC has given the Federalists a couple of weeks to reopen the oil ports or face violence, which could trigger even more unrest and a possible civil war, so this is something that extempers should continue to follow.

However, things may not be so dire for Libya’s economy as some suggest. The Christian Science Monitor on March 12th points out that Libya’s central bank has $120 billion in reserves and that number grows to $170 billion when state investments are taken into consideration. These reserves mean that the government can hold on for the next three years and finance its deficits, which gives it room to maneuver in light of Federalist activity in the East and resources to build up the nation’s military and police forces. The international community is also becoming more aware of Libya’s plight, which could lead to greater access to loans and foreign aid to get the country back on its feet (assuming that money is not siphoned off by corrupt legislators). Still, international efforts have been stalled by Libya’s political problems because a conference of Western, Arab, and United Nations diplomats in Rome received two separate delegations in mid-March with one attending with Zeidan (before he was removed from office) and another representing Islamist forces under parliamentary chief Nouri Abu-Sahmain. Without a consensus on what Libya needs most, the economy is likely to suffer and the country’s high unemployment rate is likely to continue.

Possible Solutions

As extempers can likely gather from this brief, any speech about Libya needs to address the country’s security situation since that is affecting the nation’s politics and its economy. One of the solutions to the problem is for the international community to work to train Libya’s military forces and restore them as an element of the country’s security apparatus. If the nation’s military gains the ability to overpower militia groups then the central government can extend the scope of its control. Reuters on March 26th writes that this process is already underway. Eleven U.S soldiers recently arrived in Libya to prepare Libyan forces for training exercises in Bulgaria and it is expected that Libya will send forces to be trained by Western nations over the next several years. Some Libyans believe it will take at least another three years to retrain a powerful national military, so the international community would be wise to contribute money and training resources to this project. Since Western nations decided not to put military forces on the ground in Libya (in America’s case likely because President Obama wanted to avoid putting American troops in a new combat theater after the Afghanistan and Iraq invasions of 2001 and 2003), this is one of best ways to restore stability. Also, the idea of international peacekeepers or Arab troops from one day coming to Libya is not out of the realm of possibility. CNN on March 25th reports that these troops could play a role in securing Libya’s borders, disarm militias, and even former Prime Minister Zeidan says that Western governments should have sent ground forces during the 2011 uprising to restore order after Gaddafi fell from power. However, it is highly unlikely that the U.S. will send troops to Libya and if any troops go there they will likely be part of a multinational UN peacekeeping force.

Politically, Libya needs to get its new constitution written as soon as possible. Although the Constituent Assembly elections were boycotted by minority groups, the Libyan government needs to try to make sure that the concerns of ethnic minorities are addressed in the new constitutional draft. Recognizing the different cultures in Libya and protecting their languages is the best way to ensure buy-in from these different groups and adopting a constitution that is void of hardline Islamic ideas is probably important as well so that the new government does not engender hostility from moderates in the country. Al Arabiya News on March 26th reveals that a poll by the U.S. National Democratic Institute revealed that Libyans, even those in the eastern part of the country, oppose regional autonomy and also oppose the tactics of the Federalist militia in blocking the country’s export terminals. This gives the central government some room for maneuvering the country toward a more stable path, but the constitutional draft is vital to creating confidence in democratic institutions and winning over skeptical minority groups.

This year the Rand Corporation provided a study of Libya’s various problems (along with various solutions) and I highly recommend extempers download the .pdf report. It is extensive, but provides excellent evidence for a speech on the Libyan situation. One of its recommendations is for political leaders to continue building the nation’s infrastructure and Libya needs international aid to rebuild elements of the country destroyed during its civil war against Gaddafi. It also need money to devote to projects in eastern Libya, which were devoid of investment during the Gaddafi era. Ammon News on March 19th points out that Libya is courting Jordan for investment and development projects and re-establishing Libya’s foreign relations with other governments in the region is necessary for the nation to regain its footing. The Guardian on March 17th suggests that the GNC should be allowed to govern until the summer when tensions can die down and produce a representative body that can direct these projects. The next legislative body, whether called the GNC or the House of Representatives, will have to work alongside the constituent assembly and it should try to make sure that the constitution is drafted carefully, but in a timely manner and give up power once that constitution is ratified by voters.

In summary, Libya is a country that has promise due to its oil wealth, but it needs to find ways to build other sectors of its economy so that it is not always dependent upon oil prices. It also needs to establish more of a national consensus on what type of government will rule Libya in the post-revolutionary era and gradually disarm militias and transfer power to an effective national military. The international community helped Libyans topple Gaddafi, but it needs to do more to help the country’s democratic transition. Now is not the time to give up on Libya, but to double down on commitments to ensure that the promises of the Arab Spring do not die in this area of the world.