The global financial crisis is truly a global phenomenon. A crisis that centered around a lack of credit brought about by poor judgment by financial institutions has created an international recession and the World Bank estimates that global economic growth will decline by 1.7 percent this year, the first time such a decline has existed since World War II. The Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has also weighed in on the financial crisis and backed up the World Bank’s claims in reporting that its 30 members will experience a 4.3 percent decline in growth this year.

The global financial crisis is truly a global phenomenon. A crisis that centered around a lack of credit brought about by poor judgment by financial institutions has created an international recession and the World Bank estimates that global economic growth will decline by 1.7 percent this year, the first time such a decline has existed since World War II. The Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has also weighed in on the financial crisis and backed up the World Bank’s claims in reporting that its 30 members will experience a 4.3 percent decline in growth this year.

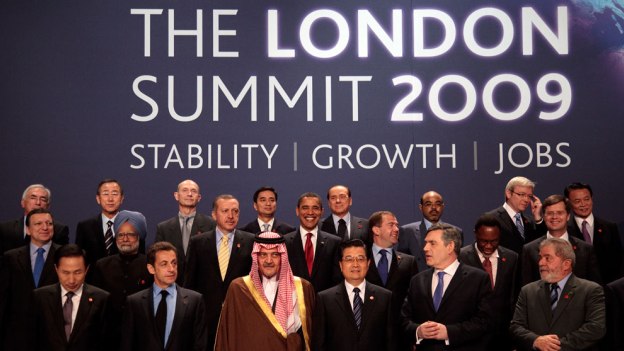

With such gloomy outlooks on the horizon, and with some financial analysts believing that governments are doing too little to stop the recession from becoming a full blown recession, the gathering of the G20 in London, an organization whose twenty members make up 85 percent of global economic output, was watched closely by international markets last week. The results of the summit ended up mixed, with the winners being the International Monetary Fund (IMF), China, and Angela Merkel of Germany and the potential losers being tighter restrictions on tax havens and most important of all, global trade.

This brief will provide some background on the G20 summit for extempers by analyzing the conflicting views that presented themselves at the summit, what the summit accomplished, and the spin and criticisms that have been leveled against the summit over the last week.

Conflicting Viewpoints

Early on it became apparent that there were significant problems that presented themselves at the summit. On one side was the United States, Great Britain, and Japan who argued that individual countries needed to boost their own economies through government stimulus packages. The argument for this was that with more stimulus money, nations could put people to work and by providing employment or cash handouts, governments might be able to stimulate spending which could revive the international market system. However, the other side of the debate, which included Germany and France, believed that new stimulus packages were not necessary and that what was needed for prevent a future financial crisis was a global financial regulator that would have the authority to seize companies regardless of national affiliation or location if they teetered on the brink of collapse and threatened the financial system. These two nations also held firm on how hedge funds and tax havens needed to be reigned in more. In the lead up to the summit, French President Nicholas Sarkozy threatened to leave the summit if it did not adopt stricter regulations of financial institutions. Eventually, a discussion of regulations was included during the meetings.

For their part, China and Russia seemed to be playing both sides and sitting out the conflict during much of the summit, although China was not keen on France’s proposal to regulate tax havens due to an impact such regulations could have in Macao and Hong Kong. Eventually with the help of Barack Obama, a compromise between these countries was reached, which will be discussed below.

Some of the conflicting viewpoints on the summit that were summarized above are tied into politics. Chancellor Merkel, regarded as one of the strongest leaders at the summit due to her public statements that she would not support another round of stimulus spending in her country, faces an election this fall and is not keen on spending too much government money due to Germany’s demographic outlook for the next several decades. The Christian Science Monitor on March 31st argued that Merkel may also have been hoping for other countries, such as the U.S. to stimulate spending so that they could “free ride” off of it without incurring any financial distress of their own. This might have played well for the chancellor because Germany’s economy is 40 percent dependent upon its exports. Also, President Obama needed to make a big impact during the summit so that he could reinforce to voters in the U.S. that he can tackle strong foreign policy issues and is doing what he can to help the economy at a time when the news about the U.S. economy continues to grow worse.

One item that was readily apparent at the summit to other leaders is that the United States took on less of a role than at previous summits. During negotiations, it appeared as if China, more than any other country, was beginning to assert itself more in discussions. Also, European powers were more of the driving force of the summit than the United States, which might augur ill for the continued domination of the United States on the global scene.

Summit’s Accomplishments

The biggest accomplishment of the G20 summit was providing more funding for the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. The G20 promised to provide the IMF and World Bak with $1 trillion in new funding with $500 billion allocated to the IMF to shore up its funds, $250 billion allocated for “special drawing rights”, which is a collection of different world currencies, for the purpose of helping developing countries, and $250 billion to help out with world trade. The summit also pledged that they would stand by these commitments to aid nation’s in need. An addition $100 billion pledge was made for developing nations which should be warmly received by those who thought that the developing world would be unnecessarily ignored in the meeting.

Furthermore, the G20 agreed to the establishment of a Financial Stability Forum that would work in conjunction with the IMF to identify future economic dangers. Cynics note, however, that experts did not forsee parts of the current economic crisis, or failed to raise significant alarm if they did, so they do not see the good of creating a global monitor for the economic system.

The G20 also promised that there would be more regulation coming for hedge funds, executive pay, and credit ratings agencies. It is believed that providing more regulation in these areas can prevent some of the serious boom and bust cycles that have taken hold of the international economy.

On tax havens, President Obama was reportedly able to hash out a deal with Sarkozy and Chinese President Hu Jintao to where the G20 would “note” the OECD’s list of world tax havens but that the G20 would not state that the list was a reflection of the G20’s viewpoints. China also got Macao and Hong Kong exempted from the OECD’s list. However, leaders did pledge to target tax havens who refuse to give government’s information when requested, which might involve financial sanctions.

Reaction

The reaction to the G20 summit is that the IMF and World Bank was a big winner and that the meeting has reinvigorated both organization’s position in handling global economic problems. Also, with the additional funding provided to the IMF, the organization has its balance sheet solidified after having to bail out nations such as Iceland earlier in the crisis and its increased plethora of resources has the ability to inspire investor confidence in the developing world and increase the scope of international markets.

Unfortunately for President Obama, he accomplished very little of what he wanted to at the summit. Obama went in hoping to negotiate a broad international stimulus, but proved unable to move Germany or France away from their refusal to provide more stimulus spending for their economies. As a result, Obama had to settle for this financial stimulus to come by way of the IMF and World Bank, which was clearly not his objective while he was at the summit. Overall, it appears that the U.S. lost out to EU demands for clearer regulation at the end of the summit. However, Obama’s team has spun the summit in a positive direction by arguing that the president did a better job than his predecessor at “listening” during the summit and was instrumental in completing the tax haven compromise between France and China.

Critics, though, argue that the summit stopped well short of taking direct action against what they consider to be the biggest problem facing the global economy: a lack of trade. The World Trade Organization (WTO) is predicting that global trade could slump anywhere from six to nine percent this year, the largest contraction of global trade in sixty years. What economists worry about is that as economies get worse, nations may believe that the way to boost them is by placing tariffs on foreign goods, something that the nation of Ecuador is already doing. These tariffs make imports more expensive and can boost domestic industries, but in doing so they can hurt other countries’ economies and spark retaliatory tariffs gradually shutting down the global trade system. A lack of global trade and rising tariffs is cited by economists as a major cause for why the global depression in the 1930s deepened, with the U.S. partly to blame with the 1930 Smoot-Hawley tariff that applied to over 2,000 imported items.

Prior to the recent summit, 17 of the countries in attendance defied agreements made at the last summit in November not to increase protectionism. The U.S. is one of the 17 violators with its recent decision to end a pilot program that allowed Mexican trucks to enter the U.S. after pressure from the Teamsters union, something that is in direct violation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and prompting retaliatory tariffs from Mexico that could cost the U.S. 40,000 jobs. Also, the U.S. subsidies for domestic car manufacturers GM and Chrysler also run afoul of the international trade system.

While the summit argued that countries should not engage in protectionism and urged the completion of the Doha trade round, they provided no specific date for Doha to be seriously negotiated. Doha can involve an accord that would open free trade across the globe, but it is bogged down by agricultural lobbies in Europe and developing countries demands that they not have to open up their industrial or commercial markets in exchange for the relaxation of Western agricultural subsidies. Also, the G20 has refused to specifically target nations who are engaging in protectionism like they want to do for tax havens. As a result, the nations who engage in protectionist economic activity feel as if they can do so with impunity.

A final criticism among Western financial experts about the G20 meeting is that the nations in attendance did nothing to urge China to move its economy more towards domestic demand so that the global economy did not have to be dependent upon U.S. consumers. In fact, economist reckon that one of the results of this crisis may be that the U.S. ceases to be the buoy of global economic growth for years to come. However, demands upon China to increase domestic demand for products or to stop currency manipulation (which some blame for causing the financial crisis by keeping interest rates in the U.S. low) most likely fell on deaf ears because the world needed China to buy into a commitment to prop up the IMF and other financial institutions (which may eventually give China a bigger voice in the organization) and because they recognize that long after the financial crisis is over, China will be more financially solvent than most of the countries in attendance at the London summit.