[fblike]

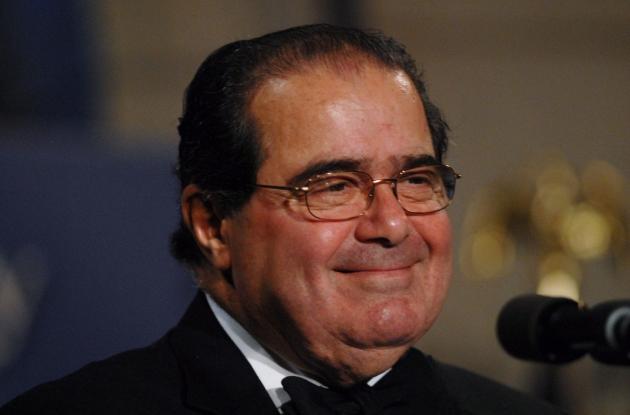

The passing of Supreme Court justice Antonin Scalia last Saturday in Shafter, Texas has thrown the nation’s political scene into turmoil. Shortly after Scalia’s death was announced, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell said that he had no intention of allowing President Barack Obama to appoint a replacement and that voters in the next presidential election should have a voice in the process. Democrats and liberals decried the statement, arguing that President Obama has a constitutional right to appoint a new justice and that the Senate must give the nominee a fair and proper hearing. Since Scalia was the leading conservative on a divided court, a liberal or progressive replacement would move the Court to the left for the first time in more than thirty years. The calculations surrounding a new nomination battle could significantly affect the outcome of the 2016 presidential election, but it could also affect cases that are currently before the Court on hot button social issues such as abortion, the Affordable Care Act, affirmative action, and voting rights. As a result, Scalia’s death comes at an inopportune time for a dangerously divided country, and the looming confirmation of a new justice could be the most divisive showdown of a judicial nominee since Clarence Thomas was barely confirmed in 1991.

The passing of Supreme Court justice Antonin Scalia last Saturday in Shafter, Texas has thrown the nation’s political scene into turmoil. Shortly after Scalia’s death was announced, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell said that he had no intention of allowing President Barack Obama to appoint a replacement and that voters in the next presidential election should have a voice in the process. Democrats and liberals decried the statement, arguing that President Obama has a constitutional right to appoint a new justice and that the Senate must give the nominee a fair and proper hearing. Since Scalia was the leading conservative on a divided court, a liberal or progressive replacement would move the Court to the left for the first time in more than thirty years. The calculations surrounding a new nomination battle could significantly affect the outcome of the 2016 presidential election, but it could also affect cases that are currently before the Court on hot button social issues such as abortion, the Affordable Care Act, affirmative action, and voting rights. As a result, Scalia’s death comes at an inopportune time for a dangerously divided country, and the looming confirmation of a new justice could be the most divisive showdown of a judicial nominee since Clarence Thomas was barely confirmed in 1991.

This topic brief will highlight Scalia’s historical significance to the Court, the impact of his death on the Court’s current term, and discuss the politics that will affect who his replacement will be.

Readers are also encouraged to use the links below and in the related R&D to bolster their files about this topic.

Scalia’s Historical Significance

Scalia was appointed to the Supreme Court by President Ronald Reagan in 1986 to succeed William Rehnquist, who Reagan had appointed to the position of Chief Justice after Warren Burger retired. Scalia came from the prestigious D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals and Reagan’s advisors liked him because of his conservative track record. Unlike Supreme Court nominations today, his appointment was not contentious and the Senate unanimously approved of his nomination (98-0). His successful confirmation made Scalia the first Italian-American to ever serve on the Supreme Court.

While on the Court, Scalia embarked on a conservative crusade against the liberal jurisprudence that dominated Supreme Court rulings in the 1960s and 1970s and was prevalent in most of the nation’s law schools. Liberals argued during this period that the Constitution was a “living document,” whereby its meaning could be interpreted differently to keep up with changes in American society. Scalia created a new school of constitutional interpretation called originalism to rebut this school of thought. According to originalism, the Constitution could only be interpreted as the Founding Fathers intended it to be. As Scalia himself noted in television interviews, this meant that if presented with a question about the constitutionality of the death penalty an originalist judge would reflect on how there was capital punishment in America in 1787 when the Constitution was created and that the prevalent form of capital punishment was hanging. If faced with the question of whether or not a form of capital punishment was unconstitutional, a judge must consider whether that method was worse than hanging. If it was, then it was unconstitutional, but if not then it was constitutional. The New Yorker noted on February 13 that originalism provided a way to justify conservative positions on social questions such as abortion rights, gay rights, and affirmative action, all of which Scalia was hostile to during his time on the Court. The doctrine of originalism proved politically polarizing and controversial, with some legal historians noting that it was an incorrect due to the fact that the framers of the Constitution never reached an agreement on what it meant (e.g. the dispute between Federalists and Jeffersonian Republicans about whether the Constitution allowed for the creation of a national bank in the 1790s). Still, the doctrine has influenced other conservative jurists throughout the country.

The second prong of Scalia’s intellectual power was the doctrine of textualism. Whereas originalism referred to constitutional law, textualism referred to interpreting statues (written laws by legislative bodies). The New Yorker writes that textualism insisted that judges look at the words of the law and not congressional “intent” or the legislative history behind a law when trying to decipher its meaning and application to a particular case. Whereas originalism was controversial on the Court, textualism appears to have thrived with The New Yorker noting that nearly all Supreme Court judges currently follow elements of it with the exception of Stephen Breyer.

When it came to major decisions, Scalia was responsible for some decisive victories for the conservative movement. Scalia interpreted the Second Amendment as giving an individual the right to possess a firearm for personal protection and this right was endorsed by the Court in the 2008 case of District of Columbia v. Heller. He also refused to endorse restrictions on campaign finance spending, viewing them as infringements of an individual’s First Amendment rights. As such, Politico reports on February 14 that he voted in the majority in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission in 2010 and this is what has caused record amounts of undisclosed political donations in elections since that time. Still, Scalia found himself in the minority in gay rights cases such as Lawrence v. Texas in 2003 and Obergefell v. Hodges last year, and was also in the minority of Casey v. Planned Parenthood in 1992 that was arguably the fiercest challenge to abortion rights since the Roe v. Wade decision in 1973. He wished to see the end of the Affordable Care Act and blasted Chief Justice John Roberts’ decision that found it constitutional in National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius in 2012. Time reports on February 13 that Scalia’s dissent said that Roberts was engaged in “Judicial jiggery-pokery” when finding that the ACA’s individual mandate was allowed under the federal government’s taxing power. Yet behind all of his dissents on these issues Scalia seemed to ridicule what he perceived as the Court settling issues that he believed the political process should solve. For him, social questions were best resolved by voters and their elected officials rather than nine justices that still do not air their proceedings on television.

However, it would be wrong for extempers to paint Scalia as an arch-conservative when they tackle questions about his legacy. USA Today writes on February 14 that although Scalia was clearly a Republican – he was overjoyed when George W. Bush triumphed over Al Gore in the 2000 presidential election that the Court had to ultimately weigh in on – he authored some decisions that protected individual rights versus a state’s police power. Scalia sided with the majority in Texas v. Johnson in 1989 that said that prohibitions on flag burning violated the First Amendment. Slate reports on February 13 that in 2011 Scalia wrote the majority opinion in Brown vs. EMA that protected depictions of violence in media and minors’ rights. In other opinions such as Kyllo v. United States in 2001 he found that police could not peep into someone’s home with a thermal imaging device and three years ago in Florida v. Jardines he reasoned that police could not use a drug-sniffing dog on private property without first securing a warrant. Slate also points out that Scalia was instrumental in bolstering an individual’s right to confront witnesses against them in court, a protection that was slipping by the 1980s.

Ultimately, Scalia’s legacy might be that he made the Court another partisan branch of government. His boisterous opinions and significance changed the way that political officials consider high court justices. Time explains that liberals came to desire their own Scalia and some, including current Vice President Joe Biden, regretted voting for his confirmation. Also, whereas presidents would once consider governors, senators, or state court judges in the past, they now prefer individuals with powerful legal minds like Scalia, which means placing a greater emphasis on law professors and those well versed in legal theory. This is partly responsible for the technocratic nature of the Court and its relative lack of diversity with regards of professional qualifications versus previous eras. However, growing partisanship surrounding the Court, which arguably began with the Robert Bork Supreme Court hearings in 1987, has also hurt the body’s reputation with 50% of Americans now telling Gallup that they disapprove of how the Court does its job.

The Legal Impact of Scalia’s Death

Scalia’s death comes at an inopportune time for the Court, which was set to rule this year on a bevy of controversial social issues. In the immediate term, Scalia’s death eliminates the Court’s conservative majority and theoretically deadlocks the Court four to four (“theoretically” is used here because Anthony Kennedy leans right, but has more of a reputation as a centrist). If that deadlock takes place during this term and the next, especially if a replacement is not appointed before the end of the year, the decisions of the lower court will stand in cases that the Court takes under consideration. The problem with this, though, is that such decisions will not create powerful legal precedent and could weaken some of the Court’s power in the short-term.

One of the issues where Scalia’s vote will be missed by conservatives is the case of Whole Women’s Health v. Cole that concerns the constitutionality of a Texas anti-abortion law. According to CNN on February 14, the law requires that abortion doctors have admitting privileges at a nearby hospital and that abortion clinics upgrade their facilities to meet hospital-like standards. Advocates of the law argue that it is necessary to protect a woman’s health in case of an emergency, but opponents say that the law is a creative way to restrict a woman’s access to an abortion. They note that if the law passes constitutional muster that only ten clinics will be available to women in the state. Scalia was expected to vote in favor of the Texas law due to his history of anti-abortion decisions, but with his vote removed it is possible that pro-choice advocates might win if a liberal appointee is confirmed. If a justice does not replace Scalia, Kennedy, a moderate on the abortion question, will have to decide the case. A 5-3 decision in favor of Whole Women’s Health would invalidate the Texas statute, but if the Court deadlocks at 4-4 it would preserve the lower court decision, which found that Texas’s law was constitutional.

Another topic where Scalia’s vote will be missed by conservative forces is Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association. This case challenges the requirement that California teachers pay fees to the state’s teachers’ union despite not being members. The case challenges the Abood case of 1977 whereby the Supreme Court declared that public employees can be required to pay nonmember fees due to the role that a union plays in negotiating new contracts and benefits that apply to all teachers, union and non-union alike. Conservatives had hoped after oral arguments earlier this year that they would win the case, especially after Kennedy was hostile towards the California Teachers Association litigants. However, Scalia’s death will probably deadlock this decision at 4-4 as well, which The Los Angeles Times says on February 14 will preserve California’s union requirements and the Abood precedent since the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals found in favor of the California Teachers Association.

Scalia’s hostility to the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was thought to have placed the law’s contraception mandate in jeopardy. The case of Zubik v. Burwell is arguing that religious non-profit corporations should not have to cover their employees contraception on moral grounds. The case is a linchpin for the growing demand for “religious liberty” in the United States and Scalia, who was a Catholic, was deemed as one of the most reliable votes in the case. His death could lead to another deadlock, but the problem with a deadlock in this case versus Whole Women’s Health or Friedrichs is that multiple circuit courts have ruled differently on the issue. In this case, the Court would have to “hold over” its decision until the next term when it may have nine judges to finally reach a decision.

Other votes that Scalia will miss include whether affirmative action is constitutional (Fisher v. University of Texas-Austin), whether voting districts should be drawn on the basis of actual population or simply the population of eligible voters (Evenwel v. Abbott), and looming decisions about whether President Obama’s executive actions on immigration and the Environmental Protection Agency’s regulations on carbon emissions are constitutional. Conservatives once thought that they would win all of these cases, but with Scalia’s death the entire calculus of the Court changes. If President Obama gets a nominee of his choosing it will move the Court in a liberal or progressive direction, especially if his nominee votes along the same lines as Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan, and liberals will win all of the cases listed.

The Politics of Replacing Scalia

If he had been able to determine his own destiny, Scalia would have preferred that he be replaced by a Republican president that would nominate a conservative. As he told Fox News several years ago, he did not want his replacement to go about undoing his work, but that is what appears poised to happen if President Obama is able to appoint a third justice as his term in office comes to a close. It was always going to be contentious when the president of the opposite party had the opportunity to pick a new justice on a very divided court and that opportunity has not presented itself in decades. President George W. Bush’s two picks of John Roberts and Samuel Alito replaced two conservative-leaning members of the Court in William Rehnquist and Sandra Day O’Connor, and President Obama’s selections of Sotomayor and Kagan replaced two liberal-leaning members in John Paul Stevens and David Souter (both of whom were appointed by Republicans but became liberals after joining the body). So now President Obama is poised, in the midst of a contentious presidential election year, to pick a judge that could shape the jurisprudence and direction of the Court for nearly a generation.

As noted in the preview of this brief, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell immediately stated that the Senate will not confirm a new Supreme Court appointee (or even hold hearings for one) until after the 2016 presidential election. The Washington Post notes on February 14 that this view has been endorsed by other senators such as Charles Grassley, who is the Senator Judiciary Committee Chairman and who would oversee any hearings on a new justice. Senators Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio, and Mike Lee (R-UT) have echoed McConnell’s position. The argument used by McConnell and his supporters is that Court vacancies should not be filled during a president’s final term, but the problem with this argument is that the Constitution provides no prohibition of a president submitting a justice for confirmation during their last twelve months in office. SCOUTS Blog writes on February 13 that there are several precedents of Congress confirming justices in an election year as the Senate has confirmed five such justices over the last century. Most recently, the Senate confirmed Anthony Kennedy in February 1988 after President Ronald Reagan nominated him in November 1987. This is the precedent that supporters of the President will likely use to charge that McConnell and others are obstructing the President in fulfilling his constitutional duties.

In adopting a position against proceeding with hearings for a new justice, the Senate Republican leadership is taking a gamble. They are hoping that a Republican can win the 2016 presidential election and that they will retain the Senate, thereby enabling them to appoint a conservative to replace Scalia. The problem here is that if they play their cards wrong and appear to defy President Obama’s apparent willingness to name a new justice that they could be deemed obstructionist. Republicans won the 2014 midterms promising to get government moving again, but they have little to show their base or the general public and this never ends up well for the party out of power when it squares off with a sitting president. The Republican situation is heightened by the fact that its Senate majority is at risk due to the fact that it is defending more seats in this cycle and some senators seeking re-election such as Mark Kirk of Illinois, Kelly Ayotte of New Hampshire, Ron Johnson of Wisconsin, and Pat Toomey of Pennsylvania are running in states that traditionally vote Democratic in a presidential year. If those senators get tarred by their opponents as obstructing the passage of a legitimate pick for the Supreme Court they could lose their races and McConnell would revert to being the Senate Minority Leader. The Republican position could also affect House races, although the Republicans have such a built-in edge due to redistricting that they should not be in a position to lose their majority this cycle. Also, the move, if it results in a Democratic president for the next four years could backfire because of the aging justices on the Court. CNN reports on February 14 that since 1960, the average age of a retiring Supreme Court justice has been seventy-nine years old, which is exactly how old Scalia was when he passed away, and there will be three judges that will be over this age by 2017 (Kennedy, Ginsburg, and Breyer). Replacing Gisnburg or Breyer would not alter the balance of the Court, but if Kennedy was replaced by a Democratic president that would give yet another vote to the liberal/progressive wing. If Republicans lose their rearguard action against the President it could doom their ability to influence the direction of the Court for the next four years, which would reverberate far beyond choosing a replacement for Scalia. Nevertheless, McConnell and other members of the “establishment” may feel that they have to stonewall because giving into an Obama pick might cause significant fractures in the Republican base. The 2016 presidential primary has already shown that the GOP grassroots is in revolt at its leadership, blaming it for doing little to stop President Obama’s agenda or hold him to account. Allowing the President to get another liberal justice onto the Court to replace a figure that was held in such high esteem by the conservative movement may be the final straw for some activists, who may not turn out to vote and doom the party’s presidential and congressional hopes in the fall.

However, the stalemate does cut two ways as the saga could benefit or hurt President Obama. On the one hand, he does have the constitutional right to choose a justice and he indicated shortly after Scalia’s passing that he intends to name a candidate. The President could name someone that is very polarizing, thereby causing the Republicans to immediately reject them on ideological grounds. This also applies to a candidate that Senate Republicans already have a tense relationship with. Such a figure could be former Attorney General Eric Holder. The Republicans could spin this as the President not working for compromise, but the Democrats could play it as the GOP unfairly targeting a minority if the President opted to pick someone with that background (e.g. a pick that was a woman, African American, Latino, homosexual, or a combination of any of the above factors). On the other hand, President Obama could go the moderate route. The New York Times writes on February 14 that compromise picks could include Sri Srinivasan, an Indian-American that was unanimously confirmed for the D.C. Circuit of Appeals nearly three years ago. The Economist adds on February 14 that Srinivasan also served in George W. Bush and Obama’s solicitor general’s office, so he has a bipartisan background. It would be difficult for senators such as McConnell, Cruz, and Rubio to suggest that they suddenly had a problem with Srinivasan after they voted for him a few years ago. Another bipartisan pick would be Jane Kelly, who was in President Obama’s class at Harvard Law School and was confirmed unanimously three years ago to the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals. However, this could work against the President’s agenda. Yes, he would get a justice, but the most progressive element of the Democratic base may revolt at the decision, arguing that President Obama needed to pick a more ideologically pure justice that represents the interests of the far-left. Also, Republicans could use the confirmation of a justice that would likely pull the Court to the left as a way to fire up its base in the presidential election, an election where polls show Republicans are far more energized than Democrats.

Whatever President Obama decides to do he must weigh whether he considers politics, his legacy, or the stability of the Court as more important. A radical pick would indicate that President Obama is more interested in securing the White House and Senate for Democrats, while a moderate pick would indicate that he was more interested in getting another liberal justice onto the Court even if that justice was not going to be as intellectually powerful as Antonin Scalia was for the conservative movement. The nominee for the Court will probably be announced within the next month and extempers should do careful research on the nominee, Senate procedures, and the history of confirmation hearings. Scalia would probably be ashamed that his death has immediately been politicized, but that is the nature of the 2016 election cycle and his passing may have a significant determination on who the next president of the United States will be.