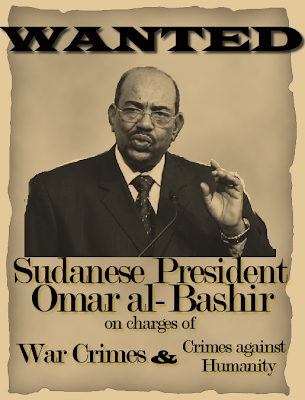

The International Criminal Court (ICC) issued its largest arrest warrant to date when last Wednesday they targeted Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir on charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity for actions that have taken place in Sudan’s Darfur region from 2003-2008. Bashir is alleged to have provided support and ordered the violence in that region of the country which has left over 300,000 people dead and displaced up to 2.5 million people. Due to the actions of Sudan’s Arab population in killing blacks farmers in Darfur, there has also been charges of genocide leveled against Bashir’s regime, although the ICC decided not to issue an arrest warrant with that charge attached.

The International Criminal Court (ICC) issued its largest arrest warrant to date when last Wednesday they targeted Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir on charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity for actions that have taken place in Sudan’s Darfur region from 2003-2008. Bashir is alleged to have provided support and ordered the violence in that region of the country which has left over 300,000 people dead and displaced up to 2.5 million people. Due to the actions of Sudan’s Arab population in killing blacks farmers in Darfur, there has also been charges of genocide leveled against Bashir’s regime, although the ICC decided not to issue an arrest warrant with that charge attached.

The arrest warrant against Bashir marks the first time that a sitting head of state has been charged with crimes against humanity and war crimes in world history. Supporters of the ICC hail this as a milestone in international justice, as it shows world leaders that they are not immune from prosecution for their acts against civilians or enemies in combat zones. Opponents of the ICC say that the arrest warrant will only further inflame disputes in Sudan and that Bashir will never be tried before the court.

This brief will break down a brief history of the ICC, so that extempers can best understand the circumstances behind the arrest warrant, explain why the arrest warrant was issued, and look into some implications for what the arrest warrant may mean for Sudan’s tenuous political situation and for future world leaders who could be targeted by the court.

ICC: A Background

The ICC came into being in 2002, when 60 nations ratified a document known as the Rome Statute. The ICC was created to handle serious charges leveled against world leaders and individuals who had committed crimes against humanity, war crimes, and genocide. The difference between the ICC and the International Court of Justice (ICJ) that had existed before is that the ICC has the jurisdiction to prosecute individuals who have committed crimes within their nation’s borders (although there are limits to this prosecution which will be discussed shortly), while the ICJ only dealt with disputes that existed across national boundaries. As another sidenote, the ICC gets its funding from the United Nations, ironically funded by countries that are not currently members (notably the United States, India, and China). Its current budget stands at $127 million.

Prior to the ICC, the United Nations had established tribunals in conflict areas such as Sierra Leone, Cambodia, and the ex-Yugoslavia to try individuals who had committed war crimes. However, these tribunals often moved slowly and were restricted over a small period of time when they did start. Critics alleged that while these tribunals had some successes, their slow movement allowed those under prosecution time to destroy evidence and intimidate witnesses (or remove them altogether) and that some criminals simply played out the clock and avoided prosecution when the time frame of the tribunal ran out. Creating a permanent court with the ICC was meant to solve these problems by having a more efficient and long running system of prosecutions that would be more reliable and set a higher standard of justice for the international community.

While the ICC is meant to go after individuals who violate fundamental human rights, its reach is limited by several factors. The ICC only has jurisdiction in cases that involve members of counties who have signed the Rome Statute, the crime in question was committed in a signatory country, or the UN Security Council asks the ICC to look into a situation. The third step is what got Bashir to this stage in the ICC process.

Another limitation on ICC prosecution is that the ICC can only try a case in its system if the nation in question is incapable or unwilling to prosecute the individual themselves.

Currently, the ICC has been criticized, especially in the developing world, as being a court of “white man’s justice” as the twelve cases the ICC is looking over all involve Africans. However, there have been calls for the ICC to look into the recent Israeli invasion of Gaza, where its jurisdiction is questionable at best since the Palestinians do not have a state of their own to claim where violations could have been committed, and even into George W. Bush’s actions, as well as his officials, in Iraq.

Why We Are Here

Bashir’s arrest warrant has been issued due to the violence that erupted in the Darfur region in 2003. Darfur is located in western Sudan and after decades of drought and overpopulation, Arab Baggara nomads, who travel the land looking for water for their livestock, and black African farmers came into conflict. Believing that the government was favoring the Arabs over the farmers, a rebellion broke out in 2003, with two rebel groups called themselves the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) and the Sudanese Liberation Army (SLA) fighting government troops and winning 34 of 38 engagements. To turn the tide, the Sudanese government began a counter insurgency strategy in the region that involved using its military intelligence wing, its air force, and a force called the Janjaweed, who were armed Baggara herders. While the Sudanese government denies having involvement in the actions of the Janjaweed, there is evidence to suggest that the Sudanese government outfitted the Janjaweed with artillery and communication equipment to make them a dangerous paramilitary force.

Shortly after invoking this strategy, the Sudanese government began to have success against the militants in Darfur. In what is often called “The Toyota War” by local combatants, because that is the vehicle of choice to get troops to battles and back, the Janjaweed began to attack civilians, displacing individuals and forcing them to flee across Sudan’s border with Chad. The Janjaweed also participated in the rape of women so that they would be shamed by their communities and killing children and infants, adding credence to international claims of genocide as these same tactics were used in Yugoslavia’s ethnic conflicts in the 1990s.

Bashir has continued to deny ordering the Janjaweed to attack civilians in the region, but when the government chose to outfit the Janjaweed as a paramilitary force it had historical evidence of what it was about to unleash. This is because in the Second Sudanese Civil War which lasted from 1983-2005, the government equipped a similar force to fight their Christian and Animist opponents in Southern Sudan and war crimes happened in that region as well with many being displaced, killed, raped, or mutilated.

What the Janjaweed have done in Darfur, with the assistance of Sudanese air superiority, has provoked the ire of the international community and leveled blame squarely at Bashir. His complicity is only reinforced by his decisions to continue attacks in the Darfur region despite UN pleas to come to the negotiating table (this was especially prevalent in 2006).

Currently, both sides are still locked in a stalemate over the situation as the Sudanese government is split by a north-south divide and Darfur’s rebel groups have split many times over. Darfur’s rebels say that they could topple Bashir by force by invading Khartoum if they wish, a charge that the government denies. Darfur’s rebels are threatening to try an invasion, though, if they do not get international support for their demands which include establishing a “no fly zone” over Darfur, allow for the same transfer of humanitarian aid from Darfur’s neighbors, and a “oil for food” program that would allow some of Sudan’s massive oil revenue to be distributed to the civilian population.

Implications of the Arrest Warrant

Most notably, Sudan is not a signatory to the Rome Statute. As such, the ICC cannot go in and have Bashir arrested on the charges they have leveled against him. However, if Bashir were to travel to a country that is a signatory to the Rome Statute then he could be sought after by the ICC and brought to trial. Bashir has joked that the ICC is not going to come and get him and have provoked demonstrations in the streets, indicating to the international community that if they try to invade Sudan to get him that he will fight them to the bitter end.

Critics suggest that the fact that Bashir may never stand trial for the charges due to Sudan not being a signatory show the weakness of the ICC’s authority. Others suggest that the ICC only charges Bashir to gain notoriety and provide a basis for future funding.

However, the biggest criticism that has been leveled against the ICC’s arrest warrant is that it could destabilize Sudan’s gentle political situation. Experts point to the fact that Sudan has expelled 14 aid agencies since the arrest warrant, something that has the potential to make the situation in Darfur even worse (and may cause another war crime charge to be tallied against Bashir), where 4.7 million people are already dependent on aid. The Bashir government seems to be following the road map set out in the Comprehensive Peace Accord it reached in 2005 with Southern Sudan which ended the Second Sudanese Civil War. This accord provides for a 2011 referendum to be held where the South has the right to secede from the central government in Khartoum if they wish. Observers worry that if it becomes clear to Southern Sudan that the Bashir government is on its last legs, they may not follow the CPA. They also worry that the Bashir government, feeling threatened, may decide to stop moving towards the referendum, something that could provoke a third civil war to break out. Bashir may also grow more radical in Darfur, a situation that has been empirically proven when the ICC went after the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) in Uganda in 2005. This caused the LRA to withdraw from negotiations with the Ugandan government and go on a murderous killing spree, something it has continued today. However, defenders of the ICC say that what makes the situation in Darfur different is that the Bashir government is already dragging its feet so its hard to imagine this arrest warrant greatly modifying the status quo.

Interestingly enough, the willingness of the ICC to target Bashir, a sitting world leader, may eventually lead to attempted prosecutions against others such as George W. Bush. This is somewhat unlikely as the Obama administration has not supported such actions, at home or abroad, and the fact that the United States is not part of the ICC. It is also unlikely because of the U.S. veto power on the Security Council. However, the fact that ICC has shown that it will not hesitate to target world leaders could open the floodgates to future prosecutions, some of which might target U.S officials.